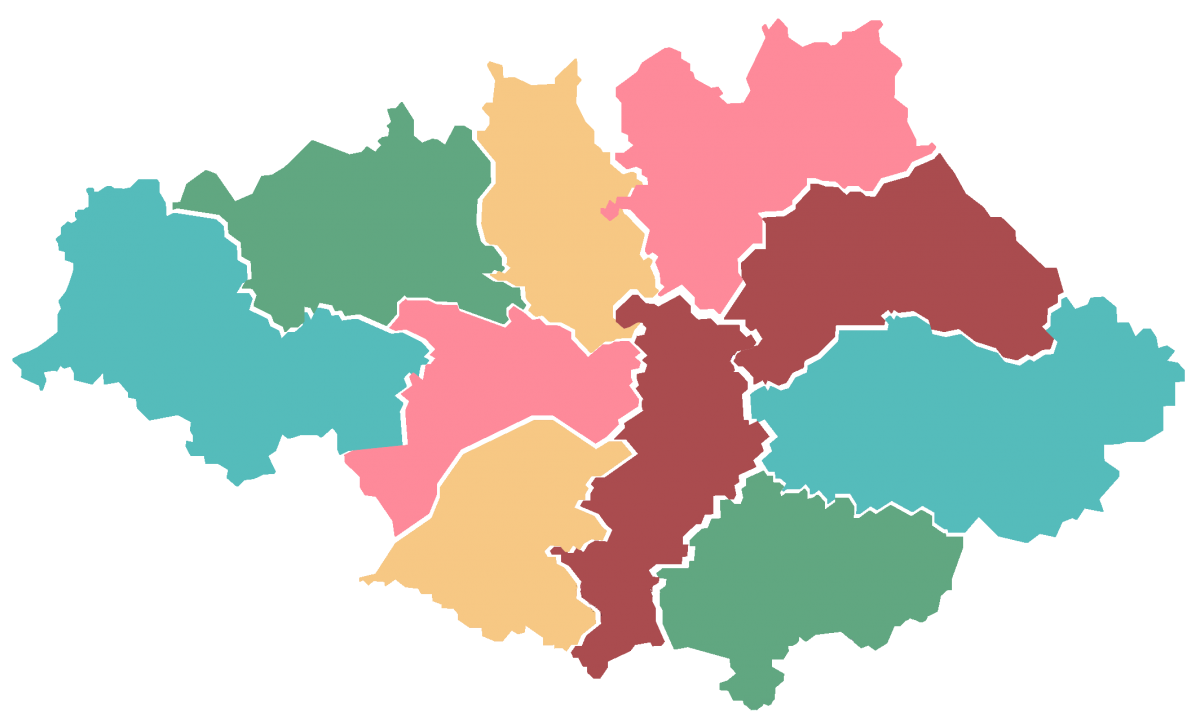

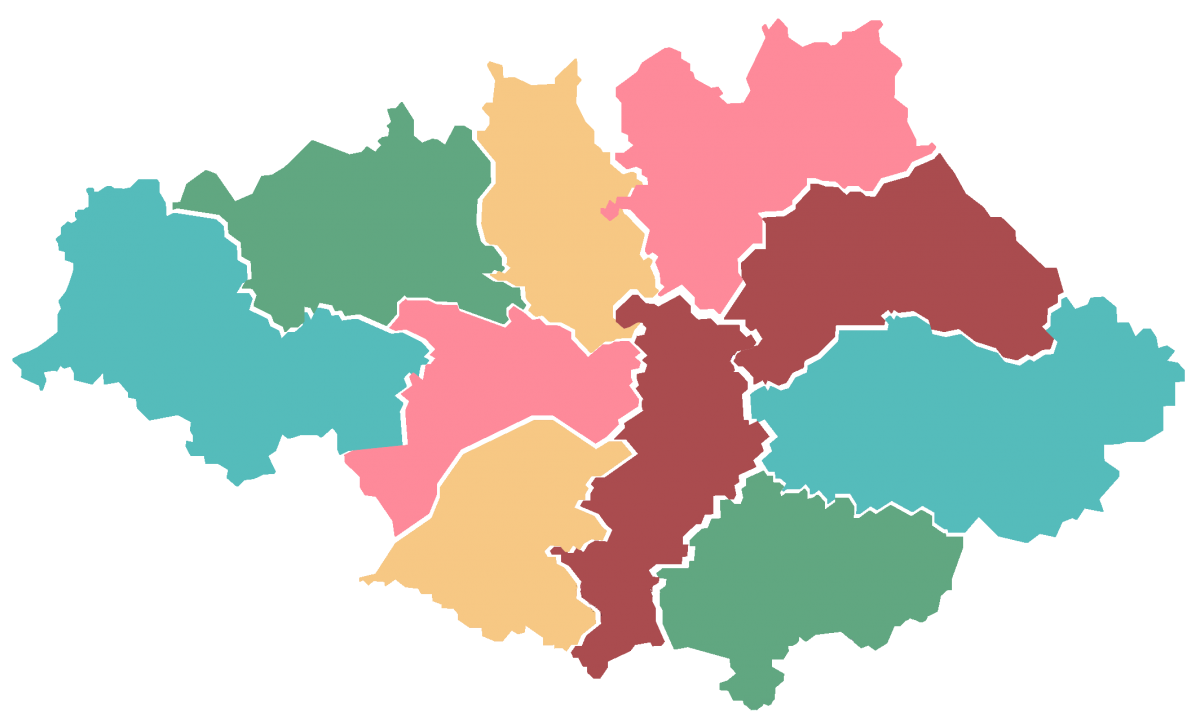

GM Cooperative Commission

GM Cooperative Commission

Making Greater Manchester the most cooperative place in the UK

GM Cooperative Commission

GM Cooperative CommissionMaking Greater Manchester the most cooperative place in the UK

by Shaun Fensom

The Internet is built on cooperation. That’s a widely understood notion that is not lost on many in the cooperative movement. That cooperatives can - even should - use digital tools like social media better to engage members is now a nostrum. That ideas like the digital commons, open source and crowd sourcing have cooperation at their heart is often cited as a reason why the 21st century could be the second cooperative century, after the 19th.

Some of us have been making these points for years. But these broad strokes miss important understandings that have fundamental implications for the future not just of cooperatives and the Internet, but for the planet.

Three facts bear close attention:

1. The Internet has driven a collapse in the cost of search (finding people to trade with) and transaction (completing the trade). This means that the ‘boundary of the firm’ described by Ronald Coase is blurring and even dissolving. Command-and-control corporations are being subverted by the very market forces they claim to champion. This creates contradictions and tensions into which new structures can - will - step.

2. This is accompanied by a shift in the role of capital. Where capital previously funded productivity gains and hence market advantage through exclusive access to new machinery, increasingly it is being used instead to consolidate first mover advantage on the Internet. Venture capital struggles to find a way to gain a return on intellectual ‘property’ because information ‘wants to be free’. A plan to make a profit by owning an idea is immediately undermined by the need to collaborate - the quickest route to market. See above for the impact on this of the blurred lines at the boundary of the firm.

3. The Internet is not a network. It is an agreement to exchange traffic between networks using shared protocols. One of the most efficient ways to exchange traffic between networks is to abandon conventional buyer-who-wants meets seller-who-has model and adopt ‘peering’ arrangements. This peering is widely mediated using a mutual model. LINX, the second largest Internet exchange in the world - a crucial component in the Internet infrastructure - is run by a cooperative. That’s not because of some commitment to freedom for data. It’s because the mutual model guarantees neutrality and hence promotes this form of collaboration.

We can draw three inferences from these observations:

The cooperative business model offers something to each of these. Where cooperatives traditionally offered a way for people to own things they otherwise could not (a combine harvester shared by farmers, a bottling plant owned by wine growers, a chain of supermarkets owned by customers), now they offer a way to mediate access and exchange, using the principles of neutrality and trust.

The Internet is built in layers. Literally. A packet of data travelling from one application to another is wrapped up and passed through a ‘stack’ before being transported across the planet and being unwrapped as it moves up the same stack at the other end. The layers can be summarised:

(There’s a parallel with the railway system: at the bottom viaducts and tunnels, rails, up through signals and trains, timetable slots and at the top, journeys).

Each of these layers forms a link in the value chain. Each involves economic operators. Some try to own the whole stack (Virgin Media), some focus on one part (Uber, Google, Openreach).

The opportunity for cooperatives to mediate access and the exchange of value can be viewed through these layers.

1. LINX strictly operates in the middle layer, but as a way of mediating access to a shared infrastructure (the links between the networks), it has similarities with cooperatives operating at the bottom layer. These are mostly new. In the UK they include Broadband for the Rural North and Cooperative Network Infrastructure (CNI), both of which apply the cooperative model to the ownership of fibre. CNI further mediates access to shared fibre for competing business members - like LINX it uses the one member one vote principle as a ‘neutrality lock’. The Brighton Digital Exchange uses a cooperative model to share access to expensive data centre facilities.

2. Cooperatives are blossoming in the top layer. CoTech brings together over 30 tech cooperatives, most of whom sell their skills while organising cooperatively. Tech workers instinctively warm to the flatter structure that motivates worker cooperatives. Many of these cooperatives are innovating in the space where the cooperative principle is key part of the business model - the notion of ‘platform cooperatives’ as an alternative to platform capitalism.

3. LINX aside, the space that is yet to attract serious cooperative engagement is the middle layer. Cloud behemoths like Amazon Web Services achieve their dominance by offering a platform that can aggregate demand for storage and ‘compute’. And yet the forces that have enabled Amazon to achieve its market dominance can equally be turned to undermine it. Simply by aggregating the same needs within the cooperative movement we could create the revenue to mount a cooperative challenge. Dreams of using ‘Principle 6’ to turbo-charge growth of the cooperative sector have foundered in the past - not least because of the need to create trust, the costs of search and transaction.

But the Internet makes this level of global collaboration feasible. We simply have to get started.

The GM Cooperative Commissioners are working to promote cooperative enterprise in Greater Manchester

This site is not published by The Greater Manchester Combined Authority