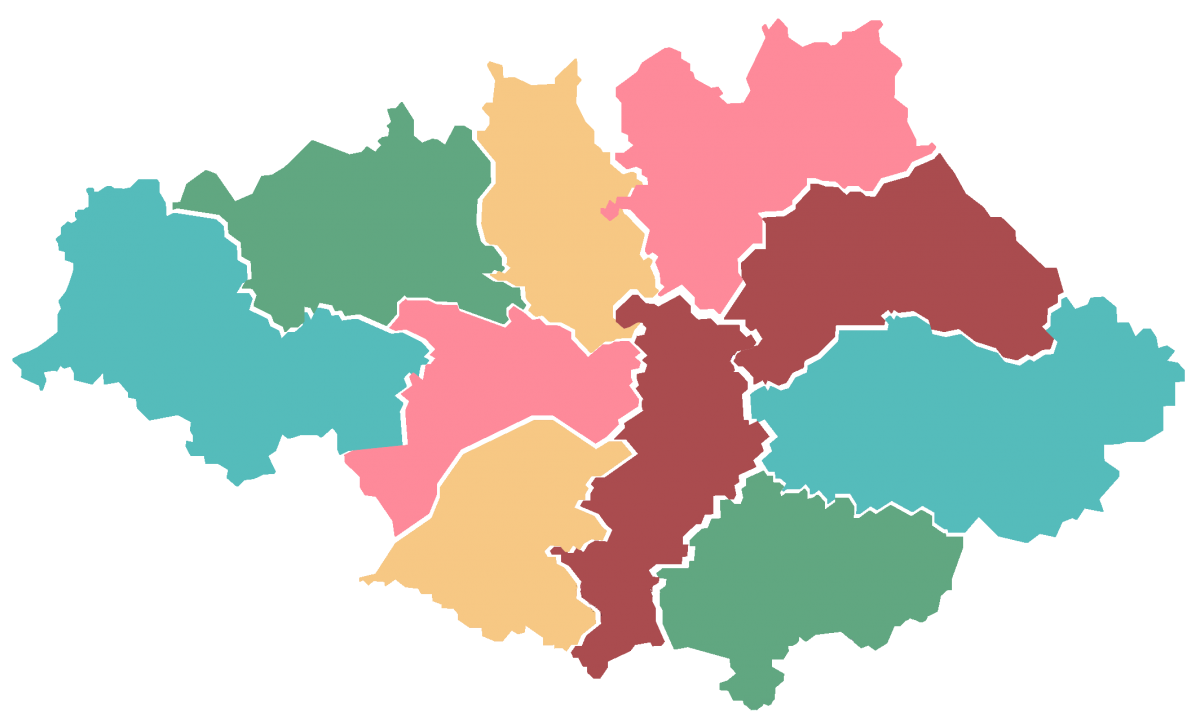

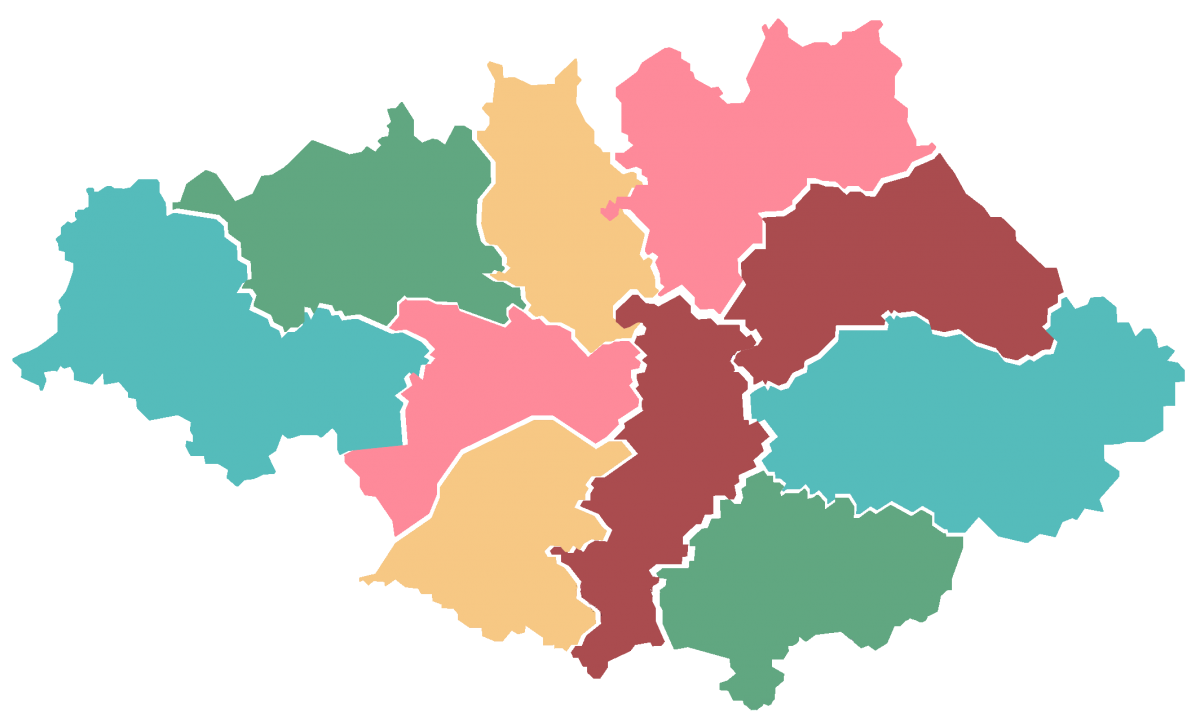

GM Cooperative Commission

GM Cooperative Commission

Making Greater Manchester the most cooperative place in the UK

GM Cooperative Commission

GM Cooperative CommissionMaking Greater Manchester the most cooperative place in the UK

“The profit motive does not sit well with care of any kind”

These are the words of Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham, at a recent event discussing care and co-operatives. The context was personal care, though they could equally apply to care of the planet as well.

They are words which will resonate with many people: care workers, those being cared for, families and friends; especially when they hear them from a former health secretary. They are worth repeating. The profit motive does not sit well with care of any kind.

But why is this the case? Why, if so much health and social care in the UK is dependent on businesses driven by the profit motive, are we in the situation where a former health secretary can say that that very system “does not sit well with care”? Most importantly, can anything be done about it?

This is not a new topic (a recent Guardian editorial poses a similar question); but it might be helpful to look at it in a new way.

Where do care and profit collide?

Every business, whatever goods or services it provides, needs three things: customers, a workforce, and finance. If any of these becomes unavailable, the business will collapse. Plus, workers need jobs, many people need care, and finance craves a profit. They all need and cannot survive without each other.

But they are also in tension with each other. Customers want to pay less or have better products for the same or less money; workers want to be paid more and have better terms and conditions; finance wants a greater reward for the risks it is taking.

Every business, everywhere, contains these tensions: between custom, labour and capital (to use Victorian language). It is a fact of life. But there are two ways of addressing it.

The route most economies have taken is to assume that those three interests must always compete with each other. So it establishes legal arrangements (companies, contracts, intellectual property), designed on the basis of competition, which provide a mechanism for trade.

This generally results in capital being the owner of enterprise, with no place or even any voice for customers or workers in the ownership and governance arrangements. It institutionalises the tension or competition, and leaves capital in control.

When interests compete with each other, they do so for their own benefit, as opposed to that of the others. Capital seeks to reward capital; competition is for the private benefit of its owners. This is where and why care and profit collide.

All forms of care sit uncomfortably with the profit motive because giving is at the heart of care, and you cannot give whilst locked into competing for private benefit.

But there is another way of addressing the tension. This involves capital, labour and custom collaborating with each other, rather than competing. Instead of a permanently competitive relationship, it seeks to establish a permanently collaborative one, treating all three interests (and other external ones) fairly, and not taking advantage of any. This is business co-operating for the common good, rather than competing for private gain.

This approach was, and to this day remains a radical alternative. It flourished in the second half of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. But the post-war settlement, the rise of large investor-owned businesses, and the demutualisation of most of the building society sector has left mutuality as a marginal part of the business landscape.

Not only is that landscape now dominated globally by investor-owned businesses trading for the private benefit of shareholders; but it has left most people with the firm belief that competitive behaviour is the only possible basis for business; and that co-operation and mutuality are quaint ideas whose time has passed.

The apparently unshakeable belief in competition and “the market" has resulted in the privatisation of many public services and left us with a care system locked into arrangements designed to produce economic outcomes, rather than care. That’s crazy, and wrong. Can it be changed?

In recent years various things have shaken the belief in competition: the financial crisis of 2007/8; the climate crisis; and social inequality. But we still fail to name the source of the problem, the real disease, and continue to treat the symptoms.

It isn’t just care of people that is incompatible with a competitive approach. In an increasingly crowded planet with limited resources, humanity cannot afford to stand by and watch competition for private gain dominate the world of enterprise or international relations.

There is another possible basis for human society. Co-operation for the common good urgently needs to be explored.

Why would Greater Manchester not want to look at this for health and social care?

Cliff Mills, Anthony Collins Solicitors, Member of the Greater Manchester Co-operative Commission

July 2022

The GM Cooperative Commissioners are working to promote cooperative enterprise in Greater Manchester

This site is not published by The Greater Manchester Combined Authority